How To Win An Argument On The Internet Without Being A Dick

If you can’t say something nice, say it in French.

Anonymous Tweet

What type of argument are we having?

When considering how to win an argument, we must first establish what type of argument we’re having. As with everything in life, the argument is not a black and white concept. It’s more of a psychedelic kaleidoscope.

Emotional vs non-emotional arguments?

All the major dictionaries give either emotional or non-emotional, rational interpretations of the word “argument.” Here are a few of them.

Dictionary definitions which do not refer to emotional involvement:

- a reason or set of reasons given in support of an idea, action or theory.

- a connected series of statements intended to establish a definite proposition.

- a reason or the reasoning given for or against a matter under discussion.

- a coherent series of reasons, statements, or facts intended to support or establish a point of view.

- a set of reasons used for persuading others.

Note the words “facts,” “reasons,” “coherent,” and “persuading.” These terms imply logic, rationality, formality, intellectual reasoning, and academic study.

The definitions above might be combined and summarised, as follows:

A coherent series of statements or facts intended to support or establish a definite proposition or point of view, with persuasive reasons given for and against the matter under discussion, whether this is an idea, an action, or a theory.

Dictionary definitions which do refer to emotional involvement

- an exchange of diverging or opposite views, typically a heated or angry one.

- a strong and sometimes angry disagreement in talking or discussing something.

- an angry quarrel or disagreement.

- angry disagreement between people.

Note the repetition of the word, “angry,” and the references to “heated” exchanges and “strong” disagreements. We might summarise the four definitions above, as follows:

A conflict or disagreement about something, which results in an angry, heated exchange of diverging or strong, opposing views.

These references to negative emotional behaviours imply a primitive instinct, whereby we lose control of our composure, abandon logic, and resort to personal insults.

Within this framework of “emotional” and “rational” definitions, a few examples of each come to mind.

Examples of “Emotionally-Driven” Arguments

- Political “point-scoring” debates in the House of Commons

- Most spontaneous arguments between lovers and family members

- Most of the disagreements that take place on social media

- School playground disagreements

- Red-top newspaper opinion pieces.

Examples of "Rationally-Driven” Arguments

- Academic essays, dissertations, theses or PhD papers

- Broadsheet newspaper opinion pieces

- Political debate in the House of Lords

- University debating society arguments

- Arguments between emotionally mature people who genuinely want to understand each other.

Rational arguments take many different forms, many of which involve complex techniques, academic study, critical thinking, and a hefty dash of philosophical enquiry to comprehend.

If you have a few years to spare, you might want to explore argument theories, where you’ll learn all about deductive arguments, inductive arguments, abductive arguments, transcendental arguments, defeasible arguments, non-arguments, analogous arguments, world-disclosing arguments, elliptical arguments, ethymematic arguments, rhetorical arguments, cosmological arguments, and practical arguments.

But, be prepared for the disappointment you’ll face when, in response to your superbly argued, thesis-length comment on Facebook, your sparring partner simply responds with one word – “dicktard.”

Discussion is an exchange of knowledge; an argument an exchange of ignorance.

Robert Quillen Tweet

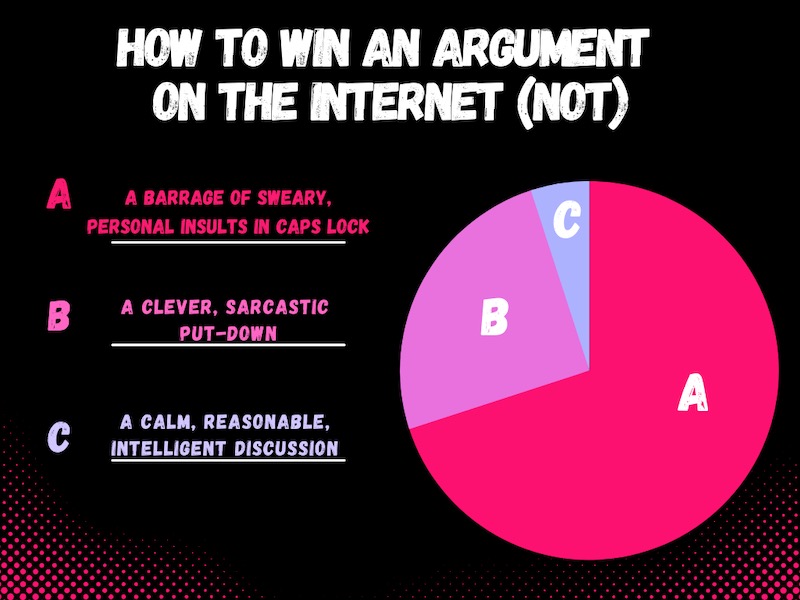

Of course, it’s possible to find both logical (rational) and illogical (emotional) types of arguments on the internet, but when it comes to social media and online forums, sadly, the emotionally-driven argument seems to occur much more frequently.

Why do people get involved in arguments on the internet?

The internet = an opinion highway network

A couple of decades ago, writers simply wrote, and readers simply read. This was a one-way channel of communication.

However, the internet has turned writing into a multi-directional conversation. Readers are able to respond and interact with writers, and each other, most notably on blogs, forums, and social media.

As a result, we are met with more personal opinions than ever before on a daily basis. Whereas before the internet, we may have encountered and interacted with only a handful of people in a single day – family members, friends, colleagues, customers, etc – on the internet, you can potentially encounter the random thoughts of hundreds of people in your social media feed.

With so many opinions to sift through, we’re bound to find that we disagree with a number of them. We are generally more motivated to respond to comments with which we disagree. After all, if you agree with something, there’s usually less to say. While you could elaborate on something you agree with, the author has probably already considered the most compelling points.

2. Communication etiquette online is quite different from that in real life.

The internet is a very public platform with innumerable communication channels, so it’s not surprising that stating a strong opinion online can often elicit a response from not just one, but potentially dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of keyboard warriors.

Given that disagreements on the internet do not occur in the flesh, the usual body language cues cannot be communicated. At the same time, the risk of a physical brawl or a violent attack occurring is greatly reduced, and this emboldens people to behave much more stridently than they would in a face-to-face argument.

When people feel physically invincible, they tend to become more opinionated and less willing to compromise. They stop listening, and refuse to even attempt to understand others’ points of view.

The result? A full-blown argument.

Does this mean that people are becoming angrier?

There has always been a risk that the sheer prevalence of disagreements online would make us angrier and more polarised. Sadly, this does seem to be the case – whether it’s Brexit, climate change, vaccines, or whether Will Smith was right to smack Chris Rock in the mouth, opinions seem to be more polarised than ever, and the level of anger appears to have escalated accordingly.

And then, of course, there are those who deliberately go out of their way to provoke arguments online. Let’s call them “arseholes” (there’s probably a much nerdier term for this already out there, but meh).

With all this disagreement happening on the internet, we could do with some sort of framework to help us engage in constructive, rather than destructive arguments. Luckily for us, programmer and writer, Paul Graham, has devised such a thing …

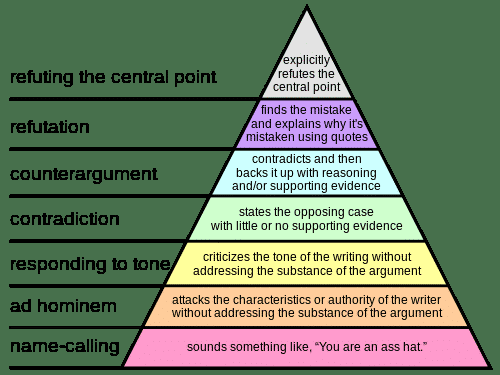

Graham’s Disagreement Hierarchy

It's easier to win an argument with a genius than an idiot.

Gurwinder Bhogal Tweet

Graham identifies seven forms of disagreement, which he sets out in the form of a pyramid-shaped hierarchy.

Graham’s Disagreement Hierarchy has the following “quality tiers” for arguments, from best to worst (or worst to best, depending on which way you look at it).

The first four bottom tiers on the Disagreement Hierarchy tend to rely on emotional provocation or manipulation, rather than valid logic, to win an argument.

1. Name Calling

The main aim of name-calling is to elicit an emotional response from your opponent. It is the lowest form of disagreement, and probably the most common. We’ve all seen comments like this:

You Brexiteers are a bunch of ignorant, racist bigots.

and:

You Remoaners are a bunch of self-righteous, self-satisfied twats.

But don’t be fooled by the more articulate forms of name-calling that can hold just as little weight. Comments like:

Those who support Brexit are usually badly-educated and ill-informed, and they have no idea what’s at stake here.

and:

Those who oppose Brexit display a sense of superiority and political correctness that renders them incapable of understanding anything beyond their woke confirmation bias …

are really just pretentious versions of “you’re a bunch of ignorant, racist bigots,” and “you’re a bunch of self-righteous, self-satisfied twats.”

Admittedly, when you’re on the receiving end of such an attack, it can often be difficult to bite your tongue and proffer a restrained and civil response. I mean, if global state leaders can’t disagree without resorting to “ours is bigger than yours” type nuclear Armageddon threats, and name-calling such as “war criminal,” “monster,” “patronising colonisers” and “bully,” what chance have the rest of us got? But, you will come out of it the better person if you do manage to resist.

Insults are the arguments employed by those who are in the wrong.

Jean Jacques Rousseau Tweet

2. Ad hominem

An ad hominem attack might actually carry a little more weight than simple name-calling, although it is still a very weak tactic to use in an argument. Internet trolls and bullies often use this rhetorical device.

It involves attacking the person (or the characteristics of the person) who is making the argument with irrelevant statements, instead of addressing their position. The aim is to undermine their credibility by killing the messenger, in the hope that the message will also disappear.

Continuing with the Brexit example, and citing a couple of real examples from Twitter, one Brexiteer argued:

“If seeing our beautiful Union Flag on a pack of British butter upsets you, maybe it’s time to seek professional help. You’re just a typical woke Remoaner.”

and one Remainer wrote:

“Your precious Brexit campaign is being led by an imbecile who has the hair of a Muppet that’s been in the dryer too long.”

Neither of these statements offer proof as to whether Brexit would be beneficial or disastrous for the British people. When people resort to ad hominem, they don’t refute an argument, but their comments are at least partially relevant to the topic in question.

If a person is upset by seeing the Union Jack on a pack of butter, a more effective argument might entail pointing out the reasons why this shouldn’t be seen as a negative symbol. And if a campaign is being led by someone with bad hair, a more sophisticated argument would involve a reasoned analysis of how the state of a person’s hair can affect their ability to make good or bad decisions.

Similarly, saying that someone is wrong because they lack the authority to write about a topic is also a type of ad hominem.

Simply stating this as a fact without examining and assessing the writer’s argument in a fair and balanced manner does not prove anything. The question should be whether the author is correct or not. If their lack of authority caused them to make mistakes, point those out. And if it didn’t, it’s not a problem.

But, it doesn’t matter if a person’s right if they’re also being an idiot. I remember reading a comment on a blog post once that went something along the lines of:

You can fling the most righteous poo in the world, but people won’t want to stand next to you because your fingers now smell of shit.

It’s a perfect analogy.

3. Responding to tone

At this level of the pyramid, we begin to see responses to what has actually been written (rather than simply attacking the writer), and many arguments and disagreements on the internet arise because a person objects to another’s tone.

This is still a weak form of disagreement, as the most important issue is whether the writer is right or wrong rather than the tone they adopt to say it. Criticising someone’s tone does not further an argument or add any value to a discussion whatsoever. It’s better that someone’s writing is boring but correct, than engaging but incorrect.

Tone is so difficult to judge on the internet. And people will always respond differently to the same tone too, depending on their existing beliefs, their personality, and their personal circumstances. Someone who has a chip on their shoulder about a particular issue might be offended by a tone that someone else would consider harmless.

4. Contradiction

At this stage of the pyramid, we finally get responses to what was said, rather than how or by whom it was said.

However, contradiction is still an inferior form of argument, as it usually involves simply stating the opposing case, with little or no supporting evidence.

Contradiction can occasionally carry some weight – for instance, when an opposing view is stated explicitly enough to make others see that it’s right. But, more often, contradiction descends into “automatic gainsaying of anything the other person says” (Michael Palin), with little or no evidence given to prove the point.

To illustrate this, here is a fabulous, well-known Monty Python sketch (featuring a very young Dawn French as the receptionist), in which a man pays to have a time-limited intellectual argument, but is greatly disappointed when his opponent insists on an argument based on contradiction alone.

In this sketch, the “Yes, I did” / “No, you didn’t” exchange dominates throughout, and is repeated no less than 28 times.

When Michael Palin’s character says “An argument is a connected series of statements intended to establish a definite proposition,” he’s quoting directly from the Oxford English Dictionary. John Cleese’s character responds brilliantly to this statement with the words, “No, it isn’t.”

Raise your words, not your voice. It is rain that grows flowers, not thunder.

Rumi Tweet

The last three forms of disagreement on Graham’s hierarchy might be described as rational argument strategies. These are:

5. Counterargument

The problem with all the previous forms of argument we’ve looked at, is that they don’t prove anything. With counter argument, we at last find a form of convincing disagreement that might actually prove something – although, it often misses the mark.

Counterargument is contradiction combined with reasoning and/or evidence (something the John Cleese character in the Monty Python sketch refused to offer). It can be an effective tactic when it’s a direct response to the opposing position. However, it is not so convincing when it’s off the mark and opponents end up arguing about two different things (often without even realising that this is what’s happening).

To return to our Brexit example, if a Remainer were to argue that the single market has enabled the EU to secure favourable terms for free trade agreements around the world for us, a Brexiteer might respond by arguing that the EU needs a free trade agreement with the UK far more than the UK needs a free trade agreement with the EU.

While these two points are related, the response doesn’t directly address the original argument, and it fails to disprove the original statement – i.e. that being in the EU has given Britain access to favourable trade agreements with countries around the world.

On occasion, there may be a case for deliberately responding with a counter argument that is slightly off tangent from the point that has been raised. For example, if you feel that your opponent has missed the crux of the matter. However, this should be pointed out to your opponent, so as to avoid any confusion.

For an argument to end well, both sides need to listen to evidence and not simply ignore things that are inconvenient for their own narrative.

6. Refutation

Refutation relies solely on evidence to prove a point, and it is one of the most convincing argument methods. It can also be very hard work to pull off successfully. This may help to explain why the higher up the disagreement pyramid we go, the fewer instances of each disagreement method we find – and this is particularly the case online.

Refutation is hard work because to refute someone you have to closely examine every aspect of their argument to pinpoint the exact place / phrase / passage where their argument falls apart.

Then, through quoting your opponent’s own words back at them, you have to deconstruct this piece of their argument to show how it’s illogical within the context of the rest of their argument, and provide evidence to prove how and why they are mistaken.

(Importantly, Paul Graham also points out that “if you can’t find an actual quote to disagree with, you may be arguing with a straw man.”).

Finally, whereas refuting an argument usually involves quoting your opponent, quoting does not necessarily mean that you are refuting. Some people quote from things they disagree with to imply that they are refuting a point, and then follow up with a response from one of the bottom tiers.

For example, Dan reads Ben’s extensive comment on all the ways Brexit is going to benefit Britain. He then pulls out and quotes one short sentence from the middle of the piece, before following up with a Tier 1 response.

BEN:

blah blah blah blah blah blah

blah blah blah blah blah blah

blah blah blah blah blah blah

blah blah blah blah blah blah

Brexit will put the Great back into Britain

blah blah blah blah blah blah

blah blah blah blah blah blah

blah blah blah blah blah blah

blah blah blah blah blah blah

DAN:

“Brexit will put the Great back into Britain.”

Yeah, right. You complete and utter dicktard!

The amount of energy necessary to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it.

Paul Kedrosky Tweet

7. Refuting the central point

And so, we arrive at the pinnacle of the pyramid, where an argument becomes a totally intellectual process. Refuting the central point is, according to Graham, the most powerful form of disagreement.

Beware of statements that look and sound like refutations, but are actually sophisticated ad hominems – for example, singling out and refuting the minor points (rather than the central point) of an opponent’s argument to discredit them personally. This might include focusing on minor typos, incorrect grammar, or spelling errors. This type of criticism has nothing whatsoever to do with progressing the argument in a constructive way.

To truly refute is to disprove or invalidate the central point of your opponent’s argument by identifying and committing absolutely to the central point.

For example:

The author’s main point seems to be that Brexit will make Britain more prosperous. He says:

“After Brexit, the billions of pounds we currently send to the EU will be spent here at home – on the NHS and salary increases for British people.”

But a study carried out by the Institute of Fiscal Studies proves this won’t actually be the case. The study includes statistics which show … etc, etc.

The quotation you choose doesn’t have to be the actual statement of the writer’s main point. It can also be enough to refute something the main point depends upon.

How can Graham’s Disagreement Hierarchy help us to have healthier arguments online?

The main benefit of the disagreement hierarchy is that it offers some perspective when interacting with others on the internet.

People whose default position is to argue against the tone of things they disagree with, may well believe they have a valid point. But if they were to take a step back and identify their position on the disagreement hierarchy, they might feel encouraged to try moving up a level or two, perhaps to counter argument or refutation.

Of course, the disagreement hierarchy levels simply describe the form of a statement used in an argument; they do not tell us whether the statement is correct. Someone who refutes their opponent’s central point might be completely mistaken, and their opponent may be the one who is correct.

Also, bear in mind that a high-level refutation still might be unconvincing, but low-level name-calling and ad hominem attacks are always unconvincing.

Unfortunately, there seem to be many more lower-tier-type arguments on the internet than higher-tier forms. They come into play when people don’t bother to employ critical thinking, and thus have nothing constructive or helpful to say.

These methods too often rely on aggressive insults or meanness, which can cause significant distress to others. The only goal of the people who use such tactics is for them to feel validated; to feel they have “won.” In short, it’s a shitty way for anyone to behave.

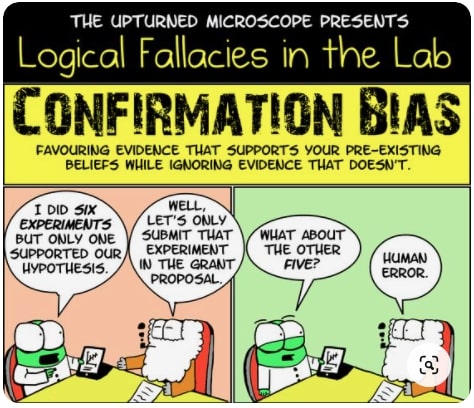

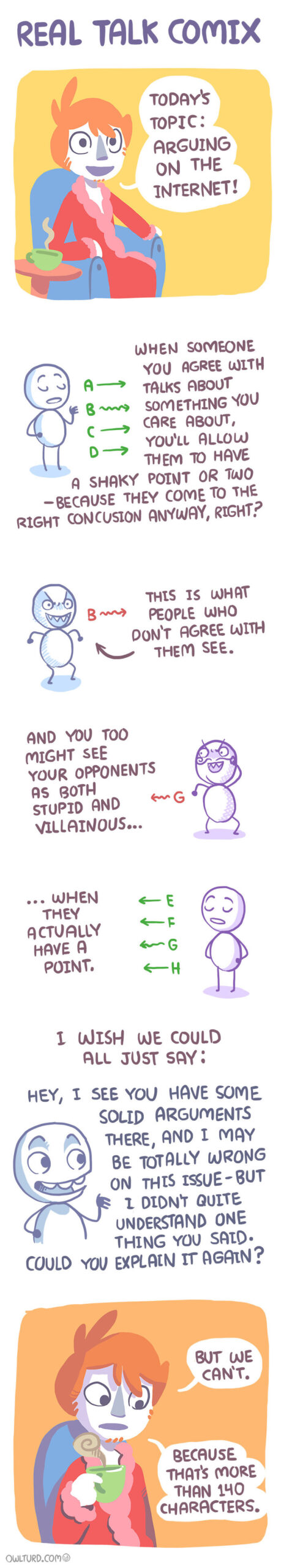

Of course, the forms of disagreement identified in Graham’s hierarchy are not exhaustive, and many other effective methods of argument exist – for example, speaking less and listening more, and practising intellectual humility can be a very effective tactic for counteracting confirmation bias.

Silence is argument carried out by other means.

Che Guevera Tweet

Beware of “The Backfire Effect”

Speaking of confirmation bias, have you ever engaged in an argument online where it seemed your opponent was incapable of accepting the truth? This may have been due to what self-acclaimed psychology nerd and author, David McRaney, calls “The Backfire Effect.”

McRaney writes about the gap between misconception and the truth.

The misconception being that “when your beliefs are challenged with facts, you alter your opinions and incorporate the new information into your thinking.”

The truth being that “when your deepest convictions are challenged by contradictory evidence, your beliefs get stronger.”

Even the 16th century author and philosopher, Francis Bacon understood this phenomenon, when 500 years ago, he wrote:

The human understanding when it has once adopted an opinion draws all things else to support and agree with it. And though there be a greater number and weight of instances to be found on the other side, yet these it either neglects and despises, or else-by some distinction sets aside and rejects, in order that by this great and pernicious predetermination the authority of its former conclusion may remain inviolate.

Francis Bacon Tweet

Some psychologists believe we do this because our ancestors necessarily focused their thoughts on real, potential threats. They may have spent more time thinking negatively than positively because threats demanded a ready response, and their survival depended on it.

This evolutionary hypothesis might explain why we tend to focus more on negative comments than positive comments today. Most of us will spend more time and mental energy responding to comments we disagree with, than those with which we agree.

The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, but wiser people are so full of doubts.

Bertrand Russell Tweet

Comments which align with our preconceived beliefs tend to slip by, barely noticed, whereas comments which threaten our beliefs jump out and grab us by the throat.

McRaney cites several studies which demonstrate how people are willing to ignore scientific evidence that invalidates their beliefs.

Worth keeping in mind next time you find yourself in an online brawl.

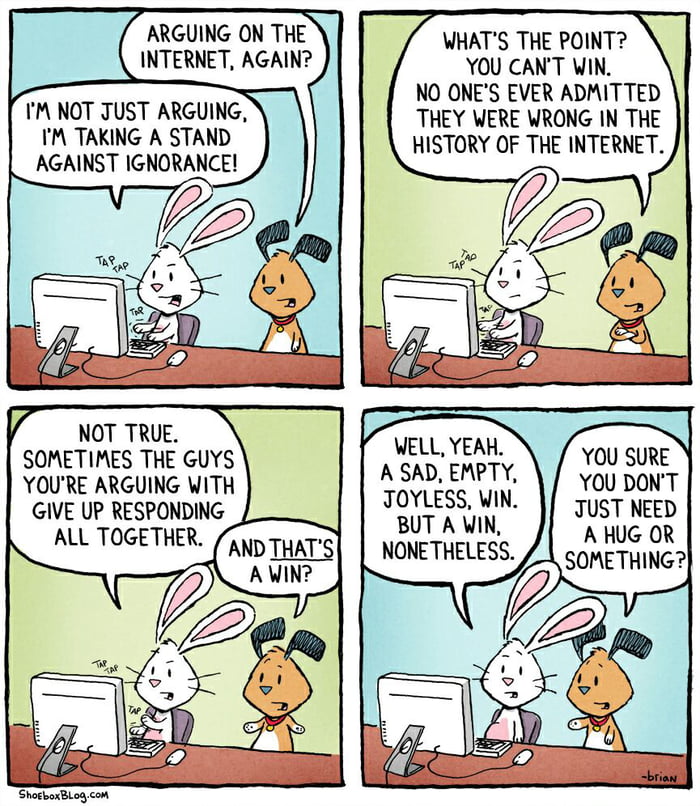

How to win an argument on the internet - a summary

- First, establish whether the argument in question is actually worth engaging with. If you don’t feel really passionate about the issue, or if it isn’t an issue that potentially affects a lot of people, then there’s probably no point expending time and energy on it. You should go and do something productive or creative instead.

2. Resist getting involved if the people who are already engaging in the argument have resorted to name-calling, slinging insults at each other, ad hominem attacks, or unhelpful, black and white contradictions, without addressing the substance of the argument.

All of these are emotional, rather than intellectual responses, and they are not worth sacrificing valuable TV time for.

No matter what you say, and no matter how eloquently you say it, you will never succeed in changing these people’s views. They have already made up their minds, and no amount of intellectual reasoning or persuasion will move them from their fixed positions.

Similarly, if you’re involved in an argument which starts out well, but begins to descend into these lower levels of the disagreement hierarchy when new participants join, then it’s time to cut loose and leave them to it.

3. Instead, engage in critical discussion with opponents who operate at the highest levels of the pyramid – i.e. refutation. People who do this stand a much better chance of influencing opinion.

4. Think about what constitutes “winning” an argument. What does that look like for you? And should winning really be the aim anyway? That old cliche, “it’s all about the journey, and not the destination” might be relevant here.

Perhaps it should be more about how we feel at the end of it. Perhaps the real question should be, “What can I learn from this argument?” rather than, “How can I win it?”

The best types of arguments offer each participant the opportunity to learn more about themselves and the world around them, and they enable people to acknowledge and understand others’ perspectives. This way, an argument can become a win/win for everyone involved.

The aim of argument, or of discussion, should not be victory, but progress.

Joseph Joubert Tweet

Finally, perhaps the greatest benefit of disagreeing at the highest levels of the pyramid is not just that it makes conversations better, but that people have a much more positive experience. After all, most people don’t really enjoy being mean; often, they do it because they don’t realise there are more effective methods out there.

So, the next time you’re about to assert your profound disagreement with the infernal heat of a million wood burners, stop and ask yourself, “Is it really worth the hassle?” If the answer is no, simply close down your laptop and go take a nice stroll in the park instead.